Stirling's Approximation

In statistical mechanics, we often deal with expressions involving the Gamma function, also know as the factorial. It is more often useful to approximate this function than to work with it directly when the function’s argument is large. Stirling’s approximation is one way to do so, let’s look at its derivation.

The factorial function \(f(n) = n!\) of an integer \(n\) is defined as the product of sequentially descending integers starting with \(n\):

\[ n! = (n)(n-1)\cdots(2)(1) \]

We can interpolate this function for values in between the integers if we want; one way to do this is via the Gamma function:

\begin{equation} \Gamma(x) = \int_{0}^\infty t^{x-1} e^{-t} \mathrm{d}t \label{eq:gamma} \end{equation}

This can be shown to be in harmony with the factorial function via integration by parts:

\[ \Gamma(x + 1) = \int_{0}^{\infty} t^x e^{-t} \mathrm{d} t \]

\[ = \left. -t e^{-t}\right|_{0}^\infty + x\int_{0}^\infty t^{x-1}e^{-t} \mathrm{d} t = x\Gamma(x) \]

Which implies that for an integer \(n\), \(\Gamma(n+1) = n!\) 1

Now we are interested in evaluating the asymptotic behavior of \(\Gamma(x)\) as \(x \to \infty\). That is, we seek an approximate function \(f(x)\) such that:

\[ \lim_{x \to \infty}(\Gamma(x)/f(x)) = 1 \]

The naive approximation would be to take only the leading term in the expansion of the factorial – e.g. since the factorial of \(x\) involves a product of \(x\) terms, we might approximate \(\Gamma(x) \approx \mathcal{O}(x^x)\) (which would overestimate, since the sub-leading term would have a minus sign in front of it). However, we can employ Laplace’s method to get a better result.

Laplace’s Method

Laplace’s method is a general method for evaluating integrals of the form:

\begin{equation} I(x) = \int_{a}^b f(t) e^{x\phi(t)} \mathrm{d} t \label{eq:laplace} \end{equation}

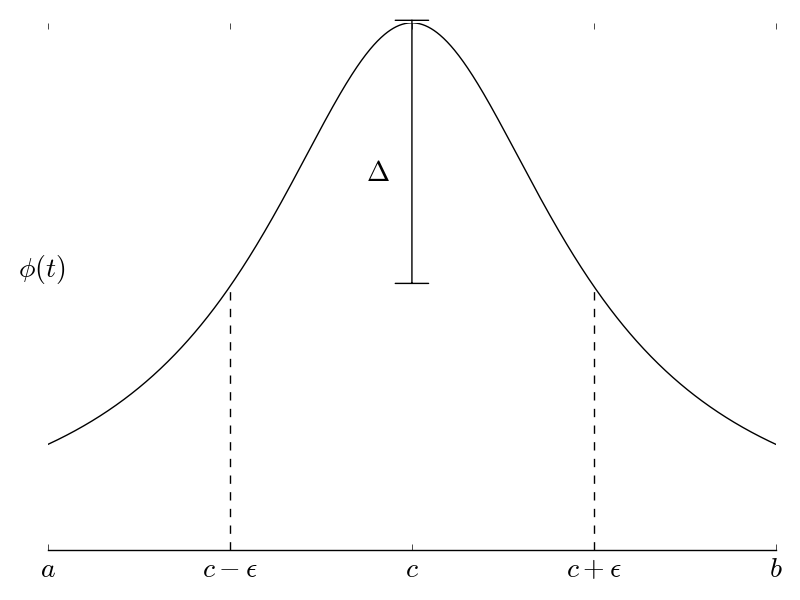

The idea behind Laplace’s method is to approximate \(\phi(t)\) to quadratic order, so that we can treat the integral as a Gaussian integral. The justification of this approximation is such: Since the integrand involves an exponential of a function \(\phi(t)\), the integrand will be strongly peaked at that function’s maximum.

If we require that the maximum of \(\phi\) occurs at some \(c\) such that \(a \leq c \leq b\) and that \(f( c) \neq 0\), then we can approximate the integral by shrinking the integration limits to within some \(\epsilon\) of \(c\):

\[ I(x) \to I(x;\epsilon) = \int_{c-\epsilon}^{c+\epsilon} f(t) e^{x\phi(t)} \mathrm{d} t \]

Now after shrinking the limits of integration, we use a Taylor series to expand the exponential function around its maximum up to quadratic order.

In our case, we have to do some algebra so \eqref{eq:gamma} is clearly in the form of \eqref{eq:laplace}. Let \(t = xy\), so that we can write 2

\begin{align*}

I(x) &= x\int_{0}^\infty \exp(x \log(xy) - xy) \mathrm{d}y \\\

&= xe^{x\log(x)}\int_{0}^\infty \exp(x(\log(y) - y))\mathrm{d}y

\end{align*}

Comparing this to \eqref{eq:laplace} we can identify \(f(t) = 1\) and \(\phi(y) = \log(y) - y\) The Taylor approximation yields: \[ \phi(y) \approx \phi(y_0) + \phi''(y_0)(y-y_0)^2 = -1 - (y-1)^2 \]

Which makes the integral:

\[ \Gamma(x) \approx xe^{x\log(x)}e^{-x}\int_{1 - \epsilon}^{1 + \epsilon}\exp(-x(y-1)^2)\mathrm{d}y \]

Final Approximation and Result

In order to get a nice, closed form expression for \(I(x)\), we note that as \(x \to \infty\), the integrand will become more strongly peaked about the maximum \(y_0 = 1\). Therefore, we expect that contributions outside of the integration limits \([y_0 - \epsilon, y_0 + \epsilon]\) to be negligible. With this, we can extend the limits of integration to \((-\infty, \infty)\) and use our knowledge of the integral of a normal distribution to evaluate the integral:

\[ I(x) \approx xe^{x\log(x) - x}\int_{-\infty}^\infty \exp(-x(y-1)^2) \mathrm{d} y = \sqrt{2\pi x}\left(\frac{x}{e}\right)^{x} \]

Therefore, for large \(n\), we can use

\[ \boxed{n! \approx \sqrt{2\pi n}\left(\frac{n}{e}\right)^n} \]

Remarks

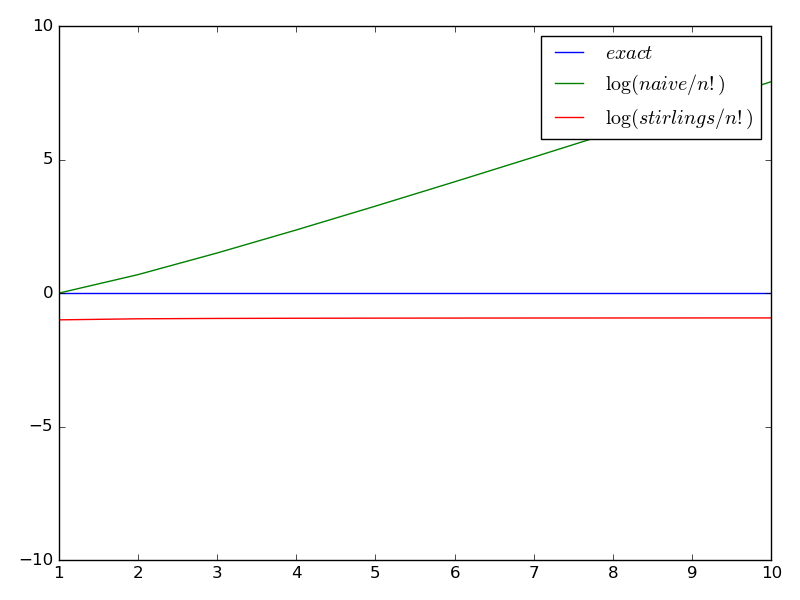

Having the result in front of us, we can compare it to the “naive approximation” for the factorial function. Stirling’s approximation says \(n! \approx \mathcal{O}(n^{n+1/2}e^{-n})\), whereas the naive approximation was \(n! \approx \mathcal{O}(n^n)\).

From the plot, we can see that it is much more accurate than the naive approximation.

Comments